The Godfather Part II (1974)

Before Sunset (2004)

The first sequel to 1979’s Star Trek: The Motion Picture benefitted from the ‘Pursuit to Algiers effect’. It had a much tighter budget than the first film – a beautiful, even poetic movie that largely lacks dramatic urgency – so director Nicholas Meyer shunned special effects wizardry for pressure-cooker drama. He staged Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan as a contest of wills between Admiral James T Kirk (William Shatner) and his titular nemesis (Ricardo Montalban) that plays out as if through submarine battles – it features few wide shots of space but many tightly framed compositions of cramped starship interiors. Meyer was more concerned with the faces of his actors than with any cosmic razzle-dazzle. And that made for one of the most cherished sci-fi movies of all time. (Paramount/Alamy)

Raiders of the Lost Ark established the template for the modern adventure film and revolutionised how action scenes are shot. But its sequel Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade goes deeper and becomes a richly layered character study, in which the whip-cracking archaeologist (Harrison Ford) and his father (Sean Connery), who’ve barely spoken in 20 years, join forces to search for the Holy Grail. The Cup of Christ isn’t used here as a mere Hollywood MacGuffin, but, like the original medieval Grail quest tales, is symbolic instead of an inward journey toward maturation. That might be due to the fact the script received an uncredited polish by playwright Tom Stoppard, who director Steven Spielberg says wrote much of the film’s dialogue. It might be the best written action movie of all time. (Lucasfilm/Alamy)

In space no one can hear you squeal for delight. The second instalment of George Lucas’ Star Wars saga (or Episode V overall) takes us to a darker end of that galaxy far, far away. Where the first Star Wars film reveled in triumph and catharsis, The Empire Strikes Back sees its heroes battered, bruised and on the run. It draws from the most elemental roots of cinema for its construction – the Battle of Hoth sequence is staged much like a DW Griffith battle scene from six decades earlier – and burns countless images in our brains: giant space worms chomping on starships, a city floating in the clouds, a spaceship rising out of a swamp, a debris field of garbage floating in the cosmic void, a smuggler caked in carbonite, a knight clutching the stump of his severed hand. The Empire Strikes Back compounded and deepened the success of Star Wars to the point that it is still the premier film franchise in global cinema. It showed that the light can shine so much brighter when surrounded by the dark. (Lucasfilm)

With thanks to BBC Culture

Some related posts:

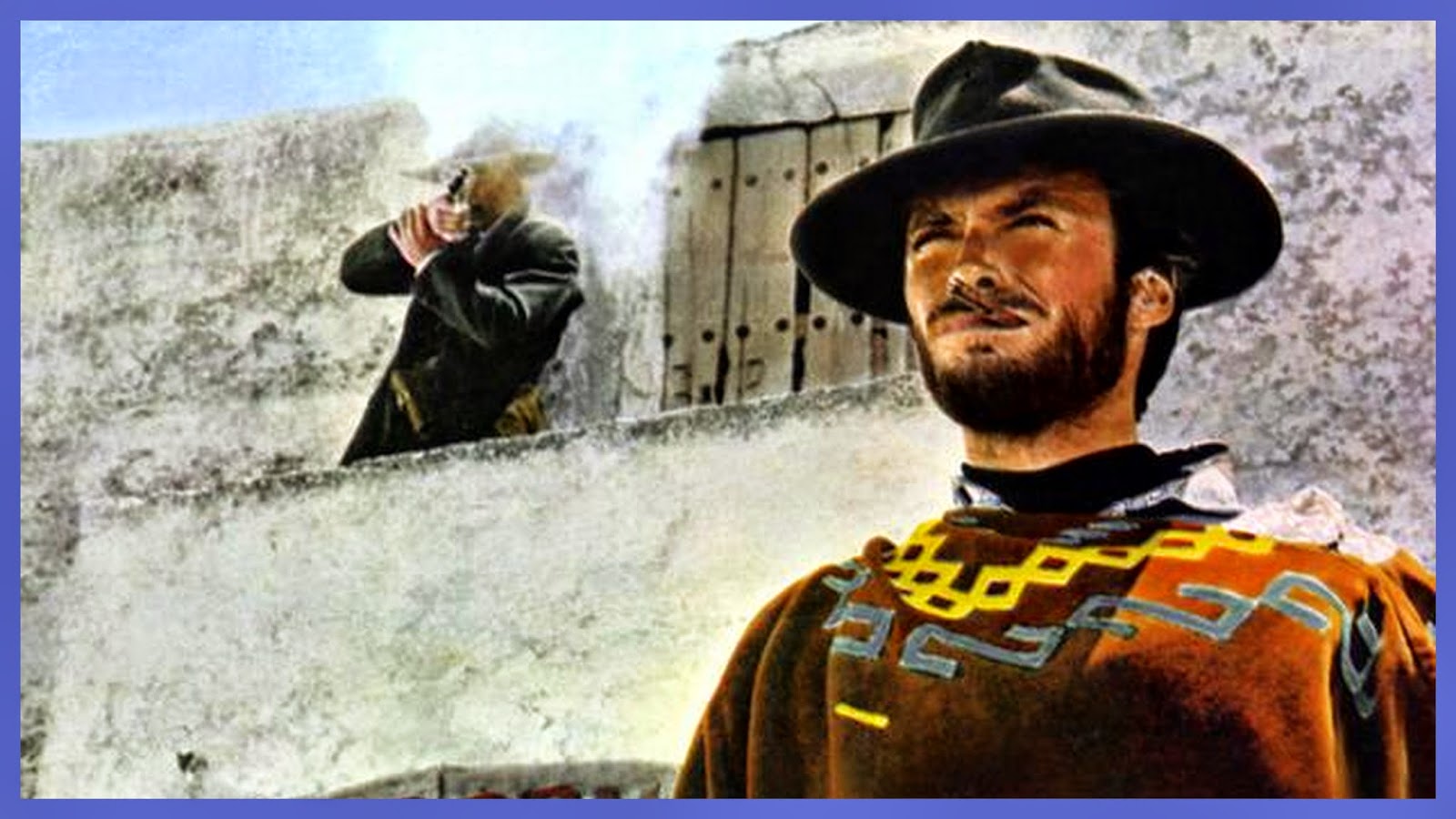

How Sergio Leone’s Westerns Changed Cinema

Top 10 Movie Twists of All Time

Oscar Winners 2016: The Full List The 100 Most Iconic Movie Lines of All Time

The Importance of Costume in Films: Some Iconic Images of our Culture

Hollywood Costume Exhibit In Los Angeles

The Splendid and Spacey World of Star Wars Posters

Star Wars Veterans Ford, Fisher and Hamill Return For New Film

The 100 Greatest Movie Characters

The Man Behind the Most Iconic Movie Posters of the ’80s and ’90s

MovieClips – Find That Unforgettable Scene

New Book: Mom In The Movies By Richard Corliss

Clint Eastwood - A True "Renaissance Man" - Updated

10 Films That Changed Filmmaking

The Book Every Movie Lover Should Own:David Thomson’s New Biographical Dictionary of Film

Hollywood's 100 Favorite Films

10 Historical Movies That Mostly Get It Right

Hans Solo's 'Chewie, We're Home' Teaser Trailer For New Star Wars Film Delights Fans

The 100 Greatest Movie Characters

Orry-Kelly:The untold story Of A Hollywood legend - "Women He's Undressed" Review

Top 10 Movie Sets Ever Built

23 James Bond Themes And How They Charted

George Lucas Defends Greedo Shooting Han First

Star Wars: How The Science Is Actually Real

New Book: Mom In The Movies By Richard Corliss

The 100 Greatest American Films

The Lasting Legacy Of The Good, The Bad And the Ugly

Are These The Top 10 Songs Named After Famous People?

Rogue One: A Star Wars Story Trailer

Famous Blondes, From Monroe and Novak To Bardot And Basinger

Clint Eastwood's Latest Biopic - Sully

10 Historical Movies That Mostly Get It Right

Long-Lost Peter Sellers Films Found In Rubbish Skip

Are These The Top 10 Comedy Actors of All Time?

New Book: Mom In The Movies By Richard Corliss

The 100 Greatest American Films

The Lasting Legacy Of The Good, The Bad And the Ugly

Are These The Top 10 Songs Named After Famous People?

Rogue One: A Star Wars Story Trailer

Famous Blondes, From Monroe and Novak To Bardot And Basinger

Clint Eastwood's Latest Biopic - Sully

10 Historical Movies That Mostly Get It Right

Long-Lost Peter Sellers Films Found In Rubbish Skip

Are These The Top 10 Comedy Actors of All Time?

Here is the list of 2015 Oscar winners.